Montana’s sexual minority youth have it rough. Despite enormous strides in acceptance and understanding there’s still much work to be done. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) youth have higher rates of suicide, mental health problems and substance abuse to name just a few issues. But policies and programs that build resiliency can be enacted so that young people can be confident in who they are without worrying about bullying, violence, job security or a lack of legal protections.

Sexual minority youth face challenges at home and in their communities as a result of stigma and discrimination – rejection by family being the most tragic outcome. It is estimated that between 20 to 40 percent of youth who become homeless each year are LGBTQ and these youth often cycle through foster homes, group homes and the streets. A review conducted by the Annie E. Casey Foundation showed that LGBTQ youth were less likely to be placed in a permanent home and were more likely to face abuse and harassment in their foster or group homes.

Suicide attempts and depression among LGBTQ youth is of grave concern. A low sense of belonging or social alienation and feeling like “an outsider” is linked to suicide. There is a startling difference among LGBTQ youth from positive, accepting families compared to those who’ve been completely rejected. Rejected youth were more than eight times as likely to attempt suicide, almost six times as likely to report high levels of depression, more than three times as likely to use illegal drugs and three times as likely to be at high risk for HIV and sexually transmitted diseases.

School-based bullying is a major problem. Sixty percent of LGBTQ students doubted they would graduate high school because of the hostile climate in their school. More than half felt unsafe because of their sexual orientation – just under half commonly avoided school bathrooms, locker rooms and gym classes. Almost one quarter were verbally harassed because of their sexual orientation and nearly all heard homophobic remarks.

LGBTQ students who’ve experienced victimization had lower grade point averages than other students and were three times as likely to have missed class because of safety concerns. LGBTQ students attending rural or small town schools, which would include most Montana schools, experienced the highest levels of victimization based on sexual orientation and gender expression.

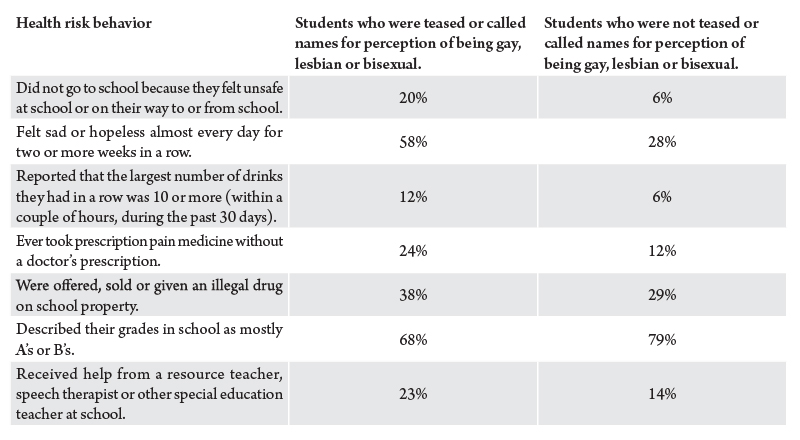

In 2015, Montana included only one question related to LGBTQ issues in the Youth Risk Behavior Survey – had the student been teased or called names because someone thought they were gay, lesbian or bisexual? Almost 11 percent of Montana high school students reported being teased or called names for that reason. Table 1 shows that these students are at greater risk than those who were not called names or teased.

For the most part Montana schools have supportive policies for LGBTQ students; as do most schools nationally. However, Montana falls well behind in several areas: teachers receiving professional development on how to teach students about different sexual orientations or gender identities, the number of schools with a gay/straight alliance or similar clubs, identifying safe spaces for LGBTQ students and the whole school staff receiving professional development on preventing, identifying and responding to student bullying and sexual harassment. Montana did slightly better than the national average in having a designated staff member to whom students could confidentially report bullying or harassment.

Secondary schools in Montana have existing practices to help students (not just LGBTQ students) who are victims of bullying. But there is a real need to educate staff specifically in the area of bullying sexual minority students. Forty-four percent of LGBTQ students reported hearing negative remarks from teachers or other school staff. Forty-eight percent of the time, neither school staff nor other students intervened when they heard homophobic remarks. Students who reported harassment or assault said that the staff took no action or told the student to ignore it. Twenty-seven percent of students were told to change their own behavior.

Social support from peers is the strongest protective factor for LGBTQ youth. While family acceptance and support also decreases the emotional and psychological distress among these youth, it was not as strong as support from their peers. There is a significant correlation between the presence of a gay/straight alliances (GSA) at a school and the reduction of self-reported cases of homophobic victimization, fear for safety or hearing homophobic remarks. Yet only 16 percent of Montana schools have any type of LGBTQ support group – nationally this number is disappointingly low at 27 percent.

Data specific to LGBTQ youth in Montana are scarce. The fact that some agencies, schools and nonprofits are serving these youth well is undeniable, however, it is based on anecdotal evidence and isolated service-specific numbers. Without such data, evidence-based policies cannot be enacted and the lack of data specific to LGBTQ youth makes progress hard. Programs and policies need to be based on facts and robust evaluations need to be conducted on programs geared to help sexual minority youth.

Why LGBTQ youth face such challenges is a political/social question and despite progress can be explained in part by the sad fact of religious intolerance, institutional homophobia, sexism, gender prejudice and antiquated views. In the 2017 Montana legislative session, a bill to add civil rights protections for LGBTQ people to the Montana Human Rights Act died in committee. Opponents argued the bill would fix a nonexistent problem, encourage immoral lifestyle choices, allow sexual predators into bathrooms and would become a weapon against conservative Christians. These claims are unsubstantiated by any evidence from other states enacting such legal protection.

Policymakers can do more to protect these vulnerable young people, but political will is still lacking to do so. Until leaders with outdated homophobic attitudes make way for the younger generations, who support inclusivity and acceptance, this will remain the case.