For decades, Montana’s largest manufacturing sector was wood products, as measured by the number of employees. Today, that position belongs to fabricated metals, with wood products falling to second and food products close behind. It’s a sign of dramatic change for a state known for its ties to the forest industry and its 20 million acres of productive, non-reserved timberland.

In 2000, wood and paper jobs were 28 percent of the state’s manufacturing employment and 31 percent of labor income. In 2016, only 13 percent of jobs and 11 percent of income was generated by wood products manufacturing.

The long decline of the wood products industry in Montana began in response to vigorous harvesting from the 1960s through the 1980s. Public campaigns to protect forest habitats, water and soil quality, and endangered species became national news.

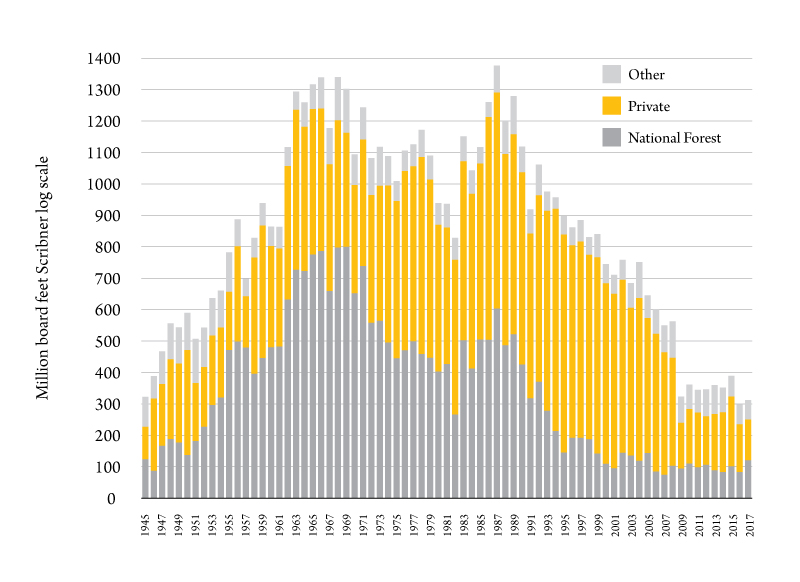

In response, the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management drastically reduced timber harvests on federal forests nationwide – nearly every western state was affected. Montana’s total timber harvests retreated from 1.3 billion board feet in 1987 to less than 300 million board feet in 2016. In the same time period, lumber production fell from 1.6 billion board feet to barely 500 million board feet, and wood product sales declined from $1.8 billion to less than $565 million.

Over the past 20 years, there has been a major shift in timberland ownership in Montana. More than half a million acres of industrial timberland has been sold and transferred to various state, federal and other nongovernmental or private landowners. Some of this timberland is no longer actively managed for timber production.

As a result, Montana has become a net importer of logs. Today, Montana mills are dependent on logs flowing in from adjacent states and struggle to get enough timber to operate at their full capacity, making it difficult to take advantage of the current booming lumber market.

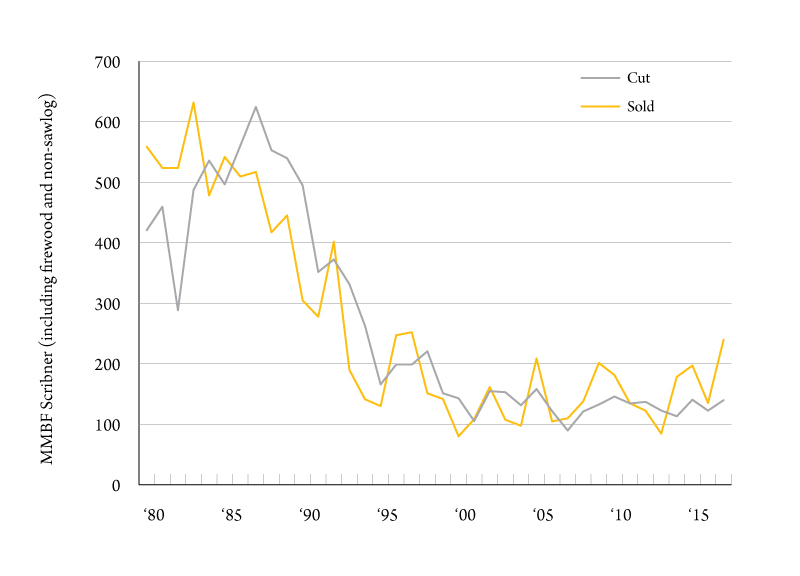

But a new national forest management strategy introduced by the U.S. Forest Service aims to increase timber harvest levels. The agency is increasing the removal of timber as a means to improve forest health and address fuel accumulation in the face of extreme wildfire seasons.

At the national level, the U.S. Forest Service’s timber harvest trend had been increasing incrementally for several years. But in 2018, their budget was reduced by nearly a billion dollars to $4.9 billion.

Acknowledging that 65 to 80 million acres of federal forests nationwide needed fire hazard reduction treatment and restoration, the current U.S. Forest Service budget earmarks $1.75 billion for forest management activities and $2.5 billion for wildland fire management.

This new budget addresses two previous forest management misconceptions: 1) forests left alone grow stronger and healthier and 2) wildfire suppression is sufficient for preventing future fires.

Forest Treatment and Collaboration

For years, forest managers witnessed the decline of forest health as active management decreased. Revenue also declined, which helps pay for other forest management and restoration costs, such as road and culvert repairs, noncommercial thinning, brush disposal or reforestation after fires or insect outbreaks.

During Montana’s 2017 fire season, nearly 1.4 million acres of forests and grassland burned. There were 35 fires larger than 1,000 acres, including the Lodgepole Complex Fire, which burned 270,000 acres near Jordan, Montana. The 160,000 acre Rice Ridge Fire on the Lolo National Forest near Seeley Lake was ranked the nation’s top wildfire priority that year.

“To decrease the risk of catastrophic wildfires and beetle kill, we are applying several treatment methods: thinning, prescribed fires and timber harvests,” said Carol McKenzie, acting director of the Forest Service’s renewable resources management for Region 1, which includes Montana, northern Idaho and smaller areas of North Dakota, South Dakota and northeast Washington.

As a result, planned timber harvests for Region 1 will increase 55 percent from 321 million board feet in 2017 to an estimated 500 million board feet in 2022. In 2017, 24,000 acres were treated, but the agency recommends treating 40,000 acres annually by 2022. “The Forest Service is increasing the pace and scale of improving forest health on forest lands. We have been talking about this for years, but in the last two years we have become very focused,” noted McKenzie.

To achieve these new harvesting goals, the Forest Service is collaborating with local governments, communities, environmental groups and industry. “Collaboration with local communities and environmental groups can help us best achieve the purpose of the restoration projects,” McKenzie explained. “With timber as the byproduct, local industry can provide a means to get the restoration done in an economic manner. In places without (forest) industry, it can be very costly to do treatments.”

Two years ago, several groups with varying opinions on forest management organized an open forum called the Montana Forest Collaboration Network (MFCN). The group now includes 22 western Montana organizations, including representatives from the wood products industry, county governments, recreational promoters and groups representing conservation, wildlife, landscape and residential interests.

The group sponsors workshops, produces reports and coordinates educational resources. But its real purpose is to help mediate conflicts regarding forest management before they become lawsuits or unwieldy policies. “Collaboration is part of the solution,” noted Tim Love, coordinator of MFCN. “We can achieve more success. We bring together science and economic incentives.”

He describes it as a push-pull strategy to avoid poor management practices. It also fosters a public reputation for transparency. “We find common ground for the broad diversity of interests. We want to keep forests as forests. It’s truly democratic,” said Love, a 40-year USFS retiree and forest planning instructor at the University of Montana.

“Nurturing longstanding relationships with the forest industry is not a new concept,” said Sonya Germann, Montana’s state forester and chief of the Department of Natural Resources and Conservation’s Forestry Division.

Germann emphasized the economic benefits to forest communities. “It’s incumbent upon us to create conditions under which industry partners can make a productive living and carry out a critical role that is understood by everyone.”

However, collaboration is not always agreeable for everyone. Julia Altemus, director of the Montana Wood Products Association, said collaboration can settle small and local issues, but it is not as successful negotiating big picture issues, such as road plans. In its quest for common ground, the collaboration process can take a long time, and not every resolution is whole heartedly approved by recreation, environmental and timber interests.

“Collaboration is essential to the forest management process. The work of keeping the public forests healthy is constantly underfunded. You can’t go in and restore thousands of acres unless you have a market,” said Altemus.

In his 2014 “Forests in Focus Initiative,” Montana Gov. Steve Bullock emphasized the importance of wood products markets in a forest restoration strategy. “Montana’s forest industry is integral to forest management, watershed restoration, wildfire risk reduction and the overall health of our forests. To ensure a stable integrated mill infrastructure in Montana, we must promote active management of forests and a sustainable timber supply.”

Public Perception and New Industry Developments

Altemus believes that the public’s love of trees is killing our forests. She has worked on policies and political debates on forest management for more than 30 years. She says that for more than 100 years forest management was guided by fluctuating social and political needs. But when public opinion rallied in defense of endangered species and in protest against perceived poor forestry practices, everything changed.

The longest-running public service advertising campaign in United States history featured Forest Service mascot Smokey Bear. His slogan, “Only YOU Can Prevent Forest Fires” spanned five decades. Unfortunately, Smokey’s call for fire suppression was not combined with forest health treatments, such as thinning overcrowded stands, prescribed burning or removing dead and dying trees. Forests were left with a bulging accumulation of flammable material.

Then forests vaulted into national politics in the wake of the 1988 Yellowstone fires, forcing the park’s first closure and again after the 2000 fire season, which left 7 million acres scorched, including 2 million acres in Idaho and Montana. Responding to the public shock, President George W. Bush proposed the Healthy Forests Restoration Act of 2003 to reduce the wildfire threat. The law increased timber harvesting and other forest management activities.

Succeeding farm bills increased funding until the 2013-14 budget allocated $500 million for wildfire fighting. It also approved the Good Neighbor Authority, which allowed state and local governments to collaborate in managing federal forests. “Over the past four or five years, more attention is being paid to fire and human safety,” said Altemus.

But in the ensuing years, Montana’s wood industry lost dozens of mills and thousands of jobs and “the surviving mills don’t run at full capacity,” she said.

However, the Forest Service’s plans to increase timber harvest levels could potentially stimulate Montana’s forest products industry. In June 2018, Victoria Christiansen, interim chief for the U.S. Forest Service, told the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, “Our anticipated level of timber harvest in fiscal year 2018 is the highest it’s been in 20 years. In all, this year the Forest Service plans to sell 3.4 billion board feet of timber while improving the resiliency and health of more than 3 million acres of national forest system lands through removal of hazardous fuels and stand treatments.” The impact could be significant since national forests account for 62 percent of Montana’s timberlands.

This recent commitment to address forest health and increase timber harvest levels is already spurring investment in Montana’s wood products industry.

This past year, the Idaho Forest Group (IFG) acquired the sawmill in St. Regis and are already planning on doubling the mill’s capacity. The proximity of the mill to Forest Service timberlands was a strong reason for its purchase. “We are already in the same wood basket,” said Tom Schultz, IFG’s vice president of government affairs.

SmartLam is a rapidly growing producer of cross-laminated timber (CLT) in Columbia Falls. Last year, they expanded their operations and moved to a new headquarters. They plan to hire 75 new employees by the end of 2019. CLT is touted as the high-tech innovation that could revive wood as the preferred material for homes and tall buildings. Buildings with CLT for ceilings, floors and walls need fewer columns and take less time to erect. Plus, the wood does not release high concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

In short, Montana’s wood products industry is on the rise once again. While the state’s forest industry production may not reach as high as in years past, there are new opportunities and hopes for lasting improvements in the health of our forests and the mills that rely on the timber.