More than 1.5 million youth in the United States experienced homelessness during the 2017-18 school year. It’s the highest number recorded in over 10 years, according to a National Center for Homeless Education report.

Housing first has become the rallying cry to address the issue. Historically, the approach has been one of managing homelessness, which has shifted to ending homelessness by providing housing. This has resulted in the federal government developing policies and funding mechanisms to avoid someone becoming unhoused by offering immediate, temporary supports to make sure a family can continue living with relatives, staying in their rental unit or elsewhere during a situation which might result in a bread winner losing their job. No matter the circumstances facing young people and their families who are experiencing a housing crisis, service providers are looking first at how to get them into housing. Once there, they can focus on other issues that might be present.

Children and youth who experience homelessness have profound challenges. In addition to stabilizing their housing situation, they need the tools and emotional support to survive without succumbing to the long-term effects of trauma. There are significant impacts on all people who experience homelessness, but children are especially vulnerable as they do not have the mechanisms to process and cope with the stress. Parental stress levels affect their children as well, especially when homelessness is a factor.

Homelessness adds a significant challenge to accessing health care and emergency rooms often become a primary source of care. Frequent moves resulting in changing addresses, lack of internet access to complete online applications, changing health care providers and lost or misplaced records, such as vaccination records or birth certificates, all create barriers.

Exposure to violence also has a dramatic effect. Children who witness violence are more likely to exhibit frequent aggressive and antisocial behavior, increased fearfulness, higher levels of depression and anxiety, and have a greater acceptance of violence as a means of resolving conflict.

Federal data from 2018 shows that in Montana there were 1,404 people experiencing homelessness – of those, 422 were families with children. Families with children represent approximately one-third of the total homeless population in both the United States and the Treasure State. In addition to families, there are 119 unaccompanied youth experiencing homelessness in our state who are under the age of 25, without a parent or a guardian.

Of particular importance to Montanans is rural homelessness – 4.4 percent of rural youth ages 13-17 and 9.2 percent of young adults ages 18-25 experience homelessness. Their biggest challenge is a lack of services. Forty-six out of 56 counties in our state are considered frontier counties – this makes access to services an added challenge. Many of these families make their way to the Montana’s urban centers where services are more available and where job opportunities are more plentiful.

Local school districts use different criteria for collecting data on unhoused school-aged children, resulting in a more accurate count. This data show that 3,606 students enrolled in public schools during the 2016–17 academic year were experiencing homelessness. Nineteen percent (692 youth) were unaccompanied youth. Calculations using both housing and school data estimate that 2,952 Montanan children under 6 years old are in families experiencing homelessness.

The impacts on these young people are well documented. Early childhood development is understood to be a major determinant in a person’s future. Healthy development in their early years (particularly birth to 3 years old) provides the building blocks for educational achievement, economic productivity, responsible citizenship, lifelong health, strong communities and successful parenting of the next generation. Experiences of homelessness during infancy and toddlerhood are associated with poor early development and educational well-being.

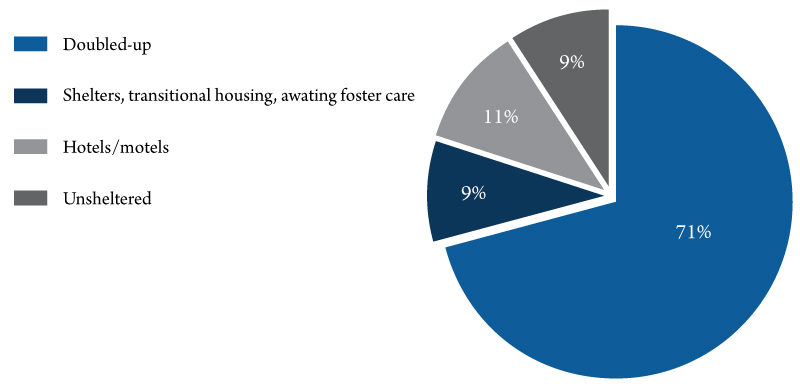

Figure 1 shows where students enrolled in public school spend their nights while they or their families were experiencing homelessness. Doubled-up refers to those young people who are living with another family. Unsheltered means students who are living in cars, parks, campgrounds, temporary trailers or abandoned buildings.

In Montana, only 67 percent of students who are considered homeless graduate from high school, compared to 86 percent of all students. Additionally, 21-23 percent of Montana students experiencing homelessness are identified as having a disability, representing 839 students in the 2016-17 school year.

To build resilience, all programs and policies should use a trauma-informed care approach, which has been shown to help all people experiencing homeless. This framework understands, recognizes and responds to all types of trauma and emphasizes physical, psychological and emotional safety. It helps survivors rebuild a sense of control and empowerment. Trauma affects the individual, families and communities by disrupting healthy development, adversely affecting relationships and contributing to mental health issues, including substance abuse, domestic violence and child abuse.

Connectedness with a parent increases student resilience and moderates the association between homelessness and negative identity or the ability to function in social situations. However, a comparison of students experiencing homelessness with their housed peers shows that only 42 percent of unhoused youth had a high connection with a parent, compared to 68 percent of housed youth. Children experiencing homelessness are seven times more likely to be placed in foster care, which brings with it a multitude of additional stresses and potentially a higher level of trauma.

The subset of unaccompanied youth experiencing homelessness needs special mention. Once homeless, youth become more vulnerable to health challenges, physical harm and abuse. It also increases their involvement in child welfare, juvenile justice, and the criminal justice systems, which often complicate their attempts to meet basic needs.

Many jurisdictions lag behind in implementing changes to federal law that strengthen access to education for youth experiencing homelessness. A few jurisdictions use words such as incorrigible, unruly, delinquent, vagrant or wayward when describing unaccompanied youth. A small number of jurisdictions define running away and truancy as status offenses and explicitly make it a crime to shelter or house a youth who has run away regardless of the reasons for the young person leaving home.

On a more positive note, many jurisdictions authorize or require health care, education and other services to unaccompanied youth even in the absence of parental consent. And most jurisdictions provide youth with some ability to act on their own behalf.

The Coordinated Entry System is used by many states, including Montana. Coordinated entry is a process developed to ensure that all people experiencing a housing crisis have fair and equal access and are quickly identified, assessed for, referred, and connected to housing and assistance based on their strengths and needs. Once an individual or family is housed, other referrals can take place to get health care and other needed services. Although still in its infancy in Montana, the goal of the Coordinated Entry System is that “all organizations in the state that serve people who are experiencing homelessness or are at risk of experiencing homelessness will participate.”

Taking a more pragmatic and informed approach, and using evidence-based interventions, such as housing first, not only improves lives but also reduces ineffective, futile public service spending. Ending homelessness requires not only a vigorous response to existing homelessness, but interventions reaching right back to the roots of homelessness. Our society must do a better job of tackling the poverty, violence, trauma, educational disadvantage and discrimination that often begins the downward spiral into becoming homeless. Until then, federal, state and local entities need to improve the crisis response. There are too few shelter programs to meet the existing need and as a result youth are regularly turned away without a place to sleep. A larger investment is needed to prevent youth from sleeping on the streets or doubling up in unstable situations and to more quickly facilitate their reunification with family when possible.