The Bureau of Business and Economic Research has been measuring and reporting on Montana’s wood products industry since the 1970s. We collect data from the mills and loggers themselves, aggregate and analyze economic data from state and federal agencies, follow articles in the popular press, and summarize and share that information through outlets like the Montana Business Quarterly, U.S. Forest Service publications and journal articles. This article examines recent developments in Montana’s forests and wood products industry and presents some comparisons with other parts of the United States.

A recent article in the Wall Street Journal did an excellent job describing why the prices that landowners in the Southeast U.S. receive for their logs did not go up when lumber prices in the U.S. spiked during late 2020 and again in early 2021 (Dezenger and Monga 2021). In short, the economic fundamentals of supply and demand played out differently in the national markets for wood products (i.e., lumber) versus the local markets for timber (i.e., logs).

During the second half of 2020, the demand for lumber used in new home construction, repairs and remodeling far exceeded the supply of lumber being produced by mills in the U.S. and Canada, causing lumber prices to rise all over the country. Meanwhile, sawmills in the Southeast enjoyed very low prices for logs from local landowners. This was due to many private landowners in that region who have been planting and growing trees for decades. The homebuilding bust of 2009 through 2012 meant a lot of timber did not get cut and was left on the stump to keep growing. Thus, the glut of available timber in the Southeast resulted in low prices for logs in the region. Even though more sawmills are being built there, the over-supply of logs is expected to exceed the capacity of mills for years to come. For many landowners the investments they made in planting and tending their forests did not yet pay off, but for mills and mill workers in that region the ample supply of logs was good news.

Folks in Montana might wonder if the same situation exists here – not so much. To understand why, we will look at a few major differences between the southern United States and Montana. The explanations are not nearly as simplistic as the climate being warmer and wetter in the South and trees growing faster.

First, land ownership is quite different in Montana than in the South. According to the U.S. Forest Service’s Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) program, which is responsible for keeping count of the nation’s forests, among the 12 states that makeup the South, less than 13% of timberland is publicly owned. Most of the public timberland is state-owned, about 30% of timberland is in corporate ownership and about 57% is owned by private individuals or families (USDA 2021).

In Montana, over 62% of timberland is owned by the U.S. Forest Service, another 5% is owned by the state, and another federal agency – the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) – owns about 4% (USDA 2021). About 29% of timberland in Montana is owned by private landowners including Native American tribes, and the amount of privately owned timberland is declining, particularly the amount of industrial timberland that is owned by companies that also own or operate mills. Different policies for public versus private ownership of timber influence those ownerships’ ability to respond to price signals from markets.

The large share of private ownership of timberland in the South has been a boon for the wood products industry in that region, enabling the growth of the South’s wood products industry during the past three decades of decline in Montana’s industry. That public-private divide has not just impacted the supply of timber, which can hardly be overstated as a major factor influencing the industry (Morgan et al. 2018). The large amount of private land ownership in the South also contributes to growth in the region’s home construction and population, which have boosted regional demand for wood products and the number of available workers. Canadian lumber companies have recognized these trends and made major investments in the South, buying and expanding mills in that region, which has a large supply of available logs, growing demand for lumber and a growing labor supply (Koenig 2019).

Before we move past land ownership as an influence on the wood products industry, let’s look at the changing ownership of Montana’s timberland and timber harvest. According to FIA, Montana had more than 1.6 million acres of industrial timberland in 1989 (Conner and O’Brien 1993). Today, approximately 800,000 acres of timberland are corporate or industrial ownership.

Substantial amounts of private industrial timberland have been sold in the past two decades. Beginning in the early-2000s, Plum Creek sold about 570,000 acres to The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and Stimson Lumber before the 2016 merger with Weyerhaeuser (Missoula Current 2020). Much of that land was resold by TNC to the U.S. Forest Service, BLM, the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation, and Fish Wildlife and Parks, as well as several private landowners. In early 2020, Weyerhaeuser sold most of its remaining Montana land – about 630,000 acres – to Southern Pine Plantations (SPP) (Weyerhaeuser Company 2020). In early 2021, SPP sold about 291,000 acres to Green Diamond Resources and another 125,800 to a married couple from Texas (Scott 2021 a,b).

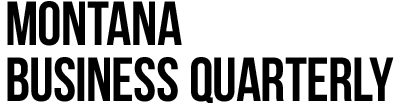

Changing private ownership of timberland in Montana is not new but has resulted in more public land and less consolidated ownership among private owners. This has raised concern among Montana’s recreation community and may create more uncertainty in timber supply for the state’s wood products industry. Timber harvest from industrial and nonindustrial private lands has been declining in recent years, while the harvest from U.S. Forest Service lands has been increasing, and state-owned harvest has been fairly consistent (Figure 1).

With COVID-related shutdowns and stay-at-home orders in effect across the U.S., many people found time for do-it-yourself and home improvement projects. Nationwide, this created additional demand for wood products. Meanwhile, the U.S. timber producing regions (i.e., the South and Pacific Coast) that provide most of the wood products, encountered production slowdowns and curtailments due to the virus’ impact on workers, supply chain disruptions and general confusion. Lumber shipments from Canada declined due to limited timber supply and reduced milling capacity in British Columbia, which contributed to U.S. wood product shortages.

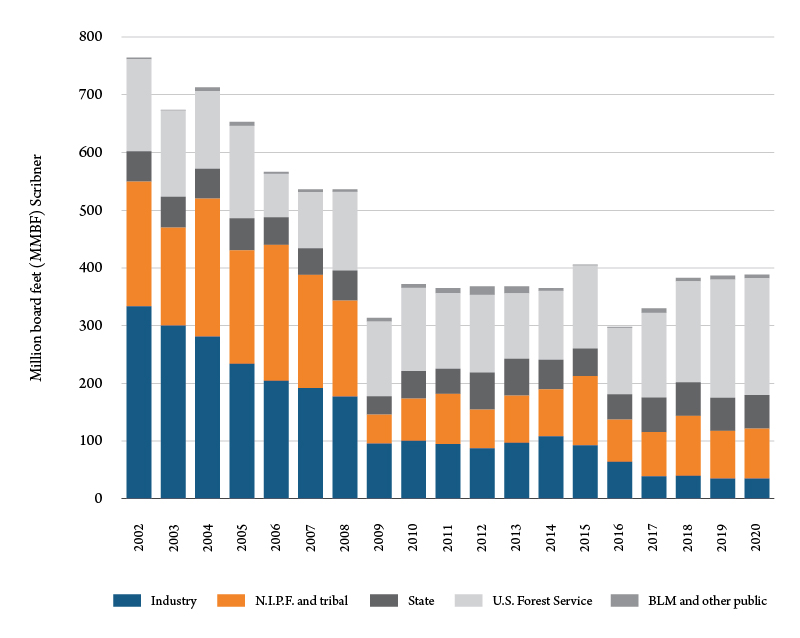

Lumber and panel markets responded with historic price spikes. The Random Lengths framing lumber composite price index increased nearly 150% from the beginning of 2020 to a record high in September, when it started to slowly decline before going even higher in early 2021 (Figure 2). In Montana, delivered log prices to mills were up 4% to 15% depending upon species from 2019, just a small increase compared to national lumber prices. However, unlike many southern landowners, Montanans did see higher log prices during 2020.

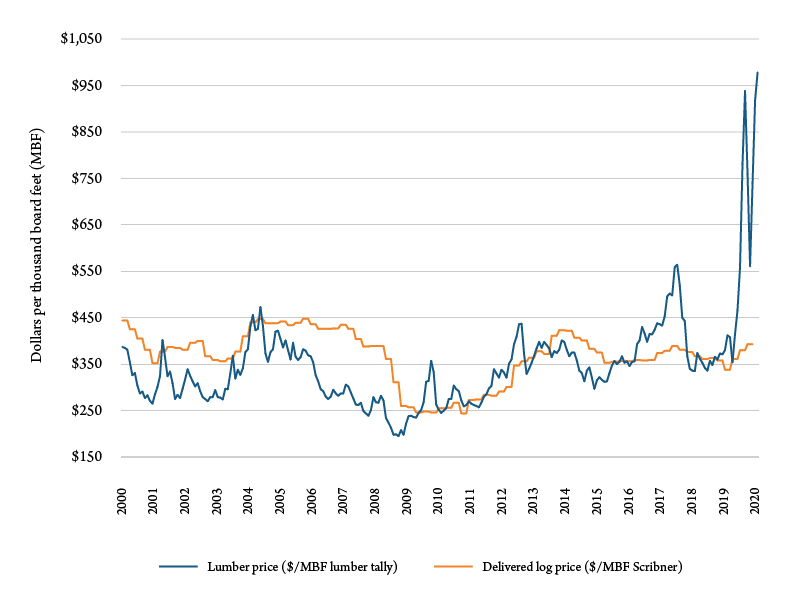

Montana mills were generally able to continue operating throughout the year. Lumber production in Montana for 2020 was 428 million board feet (MMBF), down 10.8% compared to 2019. Employment in the state’s wood products facilities was down 3%, and worker income slipped 7.8% compared to 2019 (Figure 3). However, few of these declines can be directly attributed to COVID-19. Changes at just a couple of Montana mills contributed to the employment and income differences during 2020. The R-Y sawmill in Townsend curtailed operations midyear because of a lack of log supply, which had been announced in January 2020. The Idaho Forest Group’s sawmill in St. Regis was down several months for a planned equipment upgrade, then resumed operations in August and expects to substantially increase future production.

Remarkably, sales from Montana’s industry during 2020 were up about 15% (adjusted for inflation) compared to 2019 because of the higher prices for wood products. Expectations for 2021 are generally positive. Lumber and plywood demand is expected to remain strong and prices remain historically high. New housing starts continue to increase, interest rates are low, and the home repair and remodel markets are expected to contribute to strong wood products sales. Likewise, there are positive signs for Montana on the forest management side. State and federal agencies continue to cooperate under the 2014 Farm Bill’s Good Neighbor Authority to restore forest health, reduce wildfire hazard and harvest timber to meet ecological and economic objectives.