This article digests a study of the economic contributions of the Lehrerleut branch of the Hutterite communities in Montana performed by the Bureau of Business and Economic Research at the University of Montana (BBER), in partnership with the Montana State University Department of Agricultural Economics and Economics. The study made use of a detailed financial database on the operations of a large fraction of the Hutterite communities that enabled us to track actual revenues and purchases for a three-year period.

The role of Hutterites in the local economy and the contributions made by the communities to the total economic pie are not well understood by many Montanans. The broad goal of this study is to address that information void and highlight the economic impact the Hutterite communities have on their local economies, as well as on the economy of the entire state.

About the Hutterites

Hutterites have had an important presence in Montana for more than 100 years. They are comprised of 53 communities of families with a centralized leadership structure and common ownership of land and other assets. The more than 5,000 members in our state are second in number only to South Dakota among U.S. states. The two prominent branches of Hutterites in Montana are the Lehrerleuts and Dariusleuts.

Hutterites came to North America from Europe in the 1870s as a means of escaping religious persecution. One of the oldest communal religious orders, they originally settled in South Dakota, which remains the largest concentration in the United States. The largest number of communities is in Alberta. Approximately 75 percent of Hutterites in North America are in Canada, just to the north of Montana.

Members of Hutterite communities live collectively, in groups of families governed by an elected minister. The communities collectively own land, produce and market agricultural and other goods and services, and pay taxes. Their religious orientation does not affect the tax treatment of their land and business property; in some rural communities where they operate they are the largest single property taxpayer. The fact that members of communities do not receive salaries for work done within the community does impact their federal and state income tax contributions.

In Montana the communities are largely located in the central portion of the state, east of the Continental Divide. The communities focus on farming and agriculture, including value-added production and farm-to-table distribution. They have also diversified into construction, light manufacturing and a variety of specialized products and services.

Two of the three branches of the original Hutterites who moved to North America in the 1870s have moved to Montana: the Dariusleut branch and the Lehrerleut branch. “Lehrer” is the German word for teacher and the word “leut” translates as folk or people. Of the two, Lehrerleut communities are more numerous, particularly along the Rocky Mountain front in north-central Montana.

The Lehrerleuts

This study focuses on the Lehrerleut branch of Hutterites residing in Montana. In 2017, there were 4,318 total Lehrerleut members, with 57 percent of the members between 19 and 64 years old, 33 percent less than 19 years old, and 10 percent at least 65 years old. The Lehrerleut branch members are somewhat younger than the overall population of Montana, where 60 percent of Montanans are between 19 and 64, 23 percent are less than 19, and 17 percent are at least 65 years old.

The analysis conducted in this study was based on financial records which were available for a subset of Lehrerleut communities which included 86 percent (3,749 of 4,318) of the Lehrerleut branch members in Montana. The data described and the impacts reported in this study pertain to this subset of the Lehrerleut communities, which are themselves a subset of all of the Hutterite communities in the state. Doubtless, all of the information and findings of this report would be larger than those presented here – in this sense, the findings here are conservative, since the economic activities and hence the economic impacts of all Hutterite communities is larger than those reported here.

This subset of Lehrerleut communities with financial data available has a slightly younger population profile than the Lehrerleut total. They had a higher percentage of young people less than 19 years of age (37 percent versus 33 percent); and, a lower percentage of working age people (54 percent versus 57 percent), with a similar percentage of people 65 years of age and older (9 percent versus 10 percent).

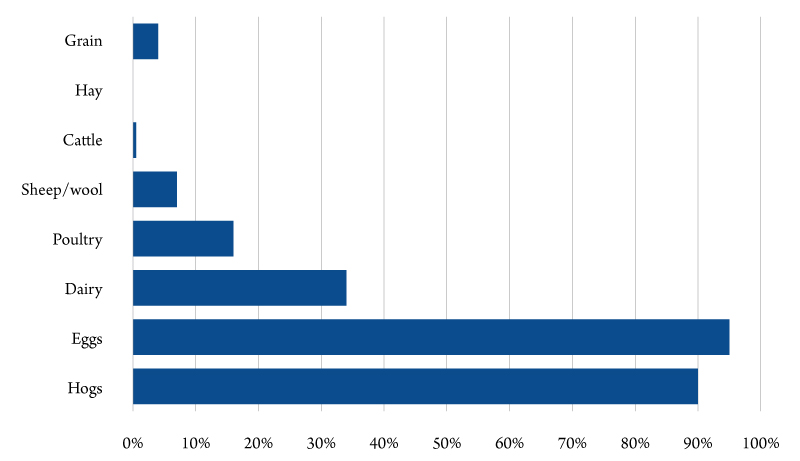

The Lehrerleut communities produce a variety of agricultural commodities. Based on cash receipts information, over 80 percent of the value of their production is derived from grain (39 percent), hogs (29 percent), and eggs (13 percent). They also generate significant cash receipts from dairy (9 percent), cattle (8 percent), and other enterprises.

The communities produce over 90 percent of the hogs and 95 percent of eggs, 34 percent of dairy and 16 percent of poultry produced in Montana (Figure 1). While they also produce grain and cattle, these enterprises make up a very small portion of the state’s overall production. The communities implement cutting-edge technologies to help promote efficiency and reduce labor requirements in their operations. These innovations along with their unique labor force have allowed them to venture into underdeveloped markets in the state, primarily in hog and egg production.

In addition to the Lehrerleut communities’ own production activities, a new collaboration with an external partner has resulted in the construction and operation of an egg-processing facility in Great Falls. The Lehrerleut communities contract with Wilcox Farms, Inc., a Washington-based egg company, is to manage the facility and purchase local production. The processing facility employees 50 workers, none of whom are Lehrerleut community members.

In addition to these agricultural activities, some communities have recently diversified into specialized manufacturing and fabrication. While mostly self-sufficient, producing everything from clothing to buildings with their own labor, they do contract with outside vendors for a variety of goods and services. The Lehrerleut communities also purchase workers’ compensation insurance for members engaged in these activities.

As owners of land and equipment, they pay substantial personal and real property taxes, and members and entities are also subject to state and federal income taxes. With respect to property taxes, the Lehrerleut communities construct substantial improvements that generate significant tax revenue which would not otherwise be realized in rural areas.

Economic Contributions of the Hutterite Communities

An economy that does not include the 81 farming operations owned by the 38 Lehrerleut communities that are analyzed in this study is clearly a smaller economy. The spending, income and production of the communities, in addition to the jobs and spending represented by the egg-processing facility that is jointly owned by 30 communities, is significant. But the contributions of the Hutterite communities to the state economy are larger than what we described in the previous section.

Our basic finding is that the presence of the 81 farming operations owned and operated by the 38 Lehrerleut communities examined in this study support production, employment and income in the Montana economy that is significant in size and scope.

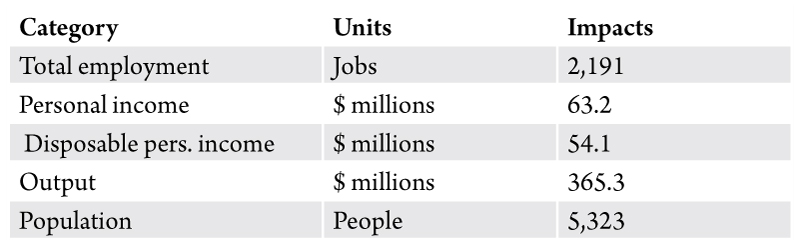

Because of the presence of the Lehrerleut communities in the state, there are:

- 2,191 more permanent, year-round jobs.

- An additional $63.2 million in income received by Montana households, annually.

- $365.3 million more gross revenue received by Montana business and non-business organizations, annually.

- More than 5,300 more people in the Montana economy.

While a large portion of these economic contributions are associated with the communities themselves, non-community businesses, workers and households reap considerable economic gains as well. This is easily seen from a more detailed look at the jobs and revenues that owe their existence to community activities. The 2,191 jobs in the overall economy that are supported by Hutterite operations in the state include significant numbers of jobs in construction, retail trade, professional business services, health care and government.

Conclusion

What would the economy of the state of Montana look like if the Hutterite communities were not present? That is the question posed in the study. Addressing this hypothetical question offers the chance to bring into clearer focus how the economic activities that take place in the 81 separate farming operations and other operations of the 38 communities interact with the rest of the economy to produce more jobs, more income, and more sales revenue for the economy as a whole.

The information is especially relevant because the rural, collective, and religious-oriented nature of Hutterite communities, together with a tradition of shunning public attention, has limited awareness of their economic importance for many Montanans.

This study took advantage of a wealth of data on the operations of the 38 Lehrerleut communities whose complete financial records were made available. The estimation of the economic contributions made use of a state-of-the-art policy analysis model, leased from Regional Economic Models, Inc. (REMI), that has been specifically constructed and calibrated for the Montana economy. While some Hutterite communities whose data were not available were not included in the estimated economic contributions, the results nonetheless demonstrate a sizable, ongoing, permanent impact of the economic livelihoods of thousands of Montanans that Hutterite activities ultimately support.