In 2015, the Montana Legislature passed the HELP Act, which expanded Medicaid for a number of low-income residents in the state. Opponents denounced the plan saying it would be a drain on the state’s economy by expanding enrollment, spending, coverage and employment. But a report by the Bureau of Business and Economic Research at the University of Montana in 2018 found it had the opposite effect. Medicaid expansion has had a substantial positive impact on Montana’s economy providing nearly $1.4 billion of health care to beneficiaries during its first two and half years.

As the Legislature was set to resume in 2019, those who continued to oppose the entitlement were asked, “How would failing to renew Medicaid expansion impact Montana’s economy?” The answer was substantial.

Prior to the debate on HB 658, a bill to extend the Medicaid expansion program, the Bureau of Business and Economic Research updated their study of its economic impact. Sponsored by the Montana Health Care Foundation and Headwaters Foundation, the study found that from 2016 to 2020, the overarching economic impact would be about $1.6 billion in additional personal income and just over $2 billion in gross state product. In 2018, Montana’s personal income was about $50 billion and gross state product was $48 billion, so the expansion would contribute about 4 percent and 3.2 percent to the state economy, respectively.

In addition, federal funding would support an additional 6,000 jobs, as well as help increase the overall population. It’s important to note that while the expansion is in the health care sector, the ripple effects are felt throughout the economy. For example, while 2,400 of the jobs are specific to the health care industry, an additional 1,000 jobs will be added to the retail sector and 600 to construction. Jobs in a variety of sectors, including food services and high-tech will be added as well.

The impacts will be felt across all regions of the state. A majority of the benefits will accrue in areas with larger population centers, such as Billings, Bozeman, Butte, Great Falls, Helena and Missoula, but rural areas will also see some economic benefits. This is particularly important given the decline in rural health care centers nationwide.

According to the National Rural Health Association, since 2010 almost 100 rural hospitals have closed their doors across the nation. More troubling is the statistic that nationally nearly 700 rural care centers are considered financially vulnerable and at a high risk of closure. The addition of over 1,000 jobs in rural regions of Montana, as well as the additional income generated, will help alleviate some of the issues facing rural hospitals.

Both studies were commissioned to analyze the economic impact of the Medicaid expansion, not necessarily the health and financial impacts of Medicaid expansion. Clearly, greater access to health care has a positive influence on physical and mental health outcomes. But there are additional benefits to improved access to health care, such as improved financial health via reduced debt, bankruptcies and better credit terms; a reduction of crime; and improvements in the health care sector overall, particularly in rural areas.

To date, no study has been conducted on the health impacts of expanding Medicaid in Montana. One of the challenges would be statistical issues that arise when conducting research on the effects of access to health care. For example, in 2008 Oregon initiated a limited expansion of its Medicaid program for low-income adults. Research found that the expansion had no significant impact on the health outcomes, using cholesterol and hypertension. However, this could also be due to the increased use of medical services, which found more incidences of medical issues.

Other research has shown that because health insurance reduces the costs of seeking care, low-income households are more likely to use clinical services, which increases the likelihood of finding potentially harmful health conditions.

Another way to look at the potential impacts of Medicaid expansion, which increases the universality of health care, is to observe health outcomes in countries which have adopted some form of universal health coverage. In developed countries, two models of health insurance have risen: the Beveridge model (found in the United Kingdom, Spain and Sweden) and the Bismarck model (found in Germany, France and Japan). In the Beveridge model, insurance is centralized in the National Health Service, i.e. Medicaid for all. While in the Bismarck model, private companies provide insurance, but prices are fixed by the government. Most countries with high incomes have adopted a version of these two models.

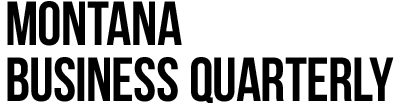

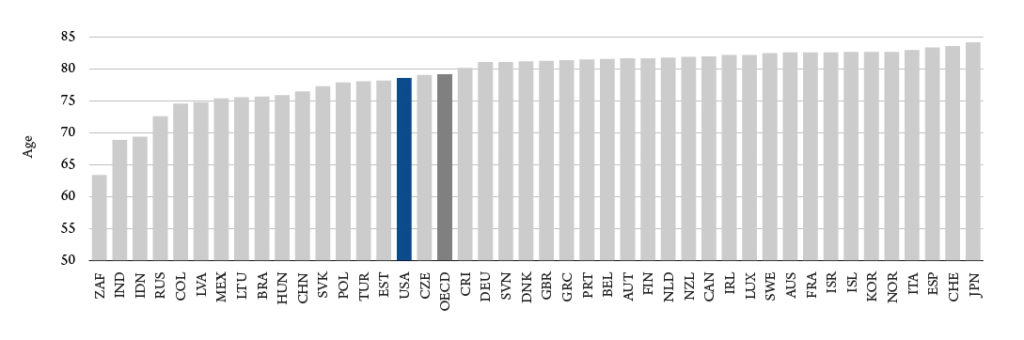

In most categories of health outcomes, countries with some form of universal care perform better than the United States and do so at a lower cost. These countries exceed in almost every category – from doctor consultations, infant mortality to life expectancy (Figure 1). The U.S. spends over twice the average of other high income countries per person (Figure 2).

This past May, Gov. Steve Bullock signed HB 658 reauthorizing Montana’s Medicaid expansion. The new law added some requirements, including a work requirement, an increase in premiums and more red tape, such as providing documentation of residency. This last requirement is especially difficult for vulnerable groups, including the homeless who may have difficulty verifying residency.

The number of Montanans that will lose coverage is expected to be about 4,100 individuals – out of approximately 100,000. Independent analysis has hinted that it will likely be higher, citing evidence from other states’ experience with work requirements. The law allows for future 1 percent enrollment growth and an enrollment audit if suspensions for noncompliance exceed 5 percent of program participants. The reduction of Medicaid enrollees will pare down some of the economic impacts presented in the study.

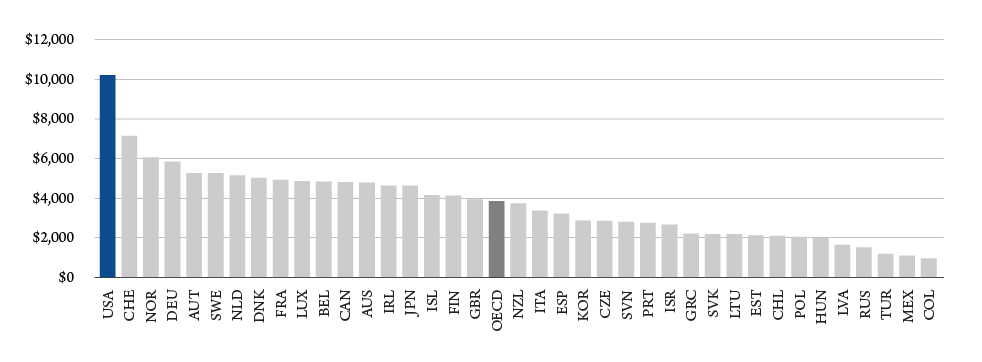

Overall, the health care industry in the state is growing. Figure 3 shows the share of total wages and employees in Montana’s hospital sector. There is a clear upward trajectory that will only increase with changes in demographics and structure.

While the new law has just taken effect, further reevaluation of the law’s economic and health impacts will be needed. If the past is any indication, health care in the state will leave an ever growing footprint on the Montana economy and we should see improving overall health over a wider swath of households.