Demand in the economy in Montana and elsewhere has roared back with unexpected speed from the pandemic declines of 2020. When you combine that surprising growth surge with the reality that public health disruptions in schools, workplaces and logistics remain with us, albeit in different forms, you have an economy that is supply constrained in a significant number of sectors.

One of those sectors is the labor market. To say that the balance of power in the give and take between workers and employers has swung toward workers in recent months would be an understatement, and that is just one of many surprises. In past recessions, employment growth lags economic growth, as employers hire back laid-off workers only after all other measures to boost output – such as working the existing workforce more hours – have been taken.

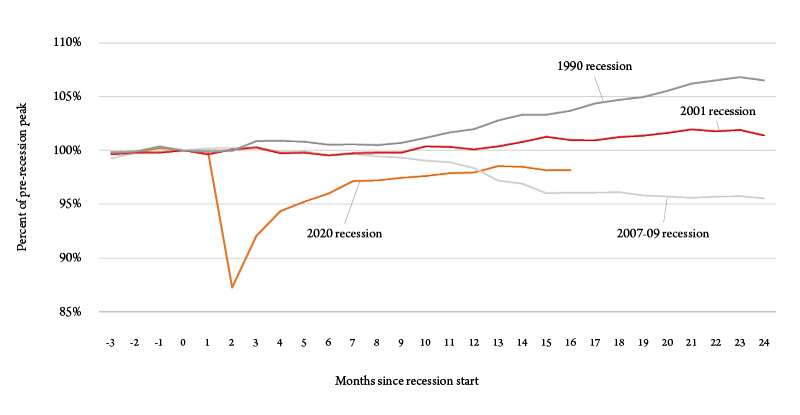

The brief but severe 2020 pandemic recession has been a completely different animal. Not only did the resumption of job growth occur in April 2020, barely two months after the February 2020 date considered to be the pre-recession peak, but the growth was strong. As shown in Figure 1, this very rapid down-up pattern of employment stands in stark contrast to the two-year-long malaise in employment that occurred during the Great Recession of 2007-09.

Now as we move through the fall of 2021, we have a mixture of circumstances that are placing heavy demands on the labor market at a time when labor supply is challenged. Not all of these are unique to this recession, but many are. They include:

- The reopening of the economy as vaccination rates rose and anxiety levels over pandemic contagion eased. The reopening was strongest in industries previously hurt the most, notably the highly seasonal and labor-intensive accommodations, restaurant and personal services industries.

- The redirection of national visitor demand from international to domestic destinations, including Montana, as international travel continued to be challenged by COVID-related restrictions. The Bozeman Yellowstone International Airport enplanements were almost 90% higher in June than pre-pandemic, the second highest increase of any airport in the country.

- The withdrawal of many former workers from the labor market for a variety of reasons, including financial security from stock market and housing wealth increases, government support payments, spousal income and COVID-related concerns.

One last factor contributing to pressure on Montana labor markets is the seasonal nature of our economy. During the summer months of any year, employment generally surges by 25,000 jobs or more as tourist volume ramps up and labor-intensive industries that serve that demand expand. The timing of the reopening of the state economy in 2021 coincided almost exactly with that seasonal peak.

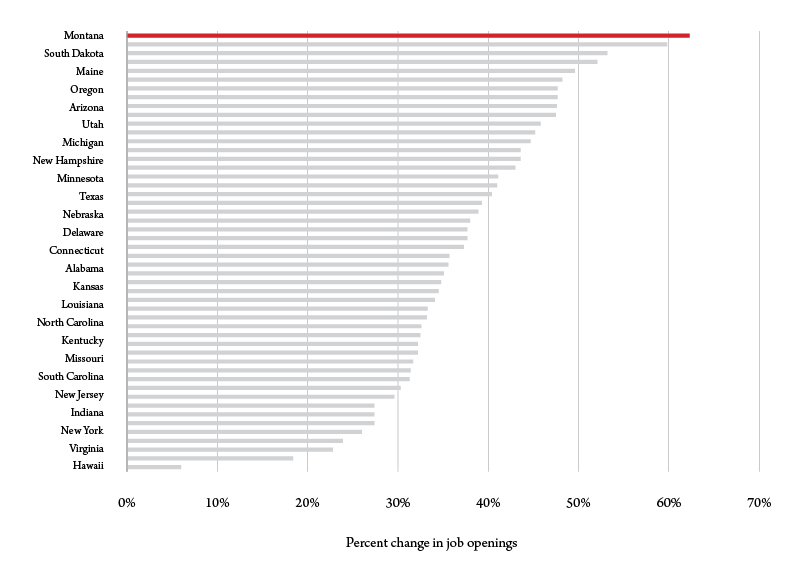

The upshot of these events has been a shortage of workers across a wide spectrum of occupations and industries in Montana that is as severe as any place in the country. By almost any measure, the scarcity of labor is apparent, particularly for entry level jobs, where increases in starting wages have been the strongest. There has been a marked increase in voluntary quits by workers, a sign of their confidence in future job availability. And speaking of availability, the 62% increase in job openings experienced in Montana since before the pandemic began was higher than any state (Figure 2).

Labor Shortages Forever?

The labor shortages being experienced by Montana employers in 2021 reflect the fact that labor markets take time to adjust to major events like recessions and reopenings. The immediate resumption of demand for workers after more than 50,000 jobs were destroyed in the span of two months in 2020 was a surprise to workers and employers alike. Each anticipated employment separations of a longer duration than actually occurred. Employers let skilled workers go, to their profound regret, and workers used their employment hiatus as a time to consider other kinds of jobs or even retirement.

It is easy to forget in the upheaval of the past year and a half that the state economy entered this recession with employers expressing plenty of anxiety about labor force availability. The forces that helped produce those pre-pandemic concerns have not fundamentally changed. Demographic events like falling birth rates and the retirement of baby boomers, coupled with huge disruptions in international migration, are stagnating the growth of the working-age population. And the shift in the interests and desires of Generation Z workers just entering the labor market continues to work against the needs of employers in less desired trades and construction occupations.

That’s why the lists of action steps that employers and policymakers might consider to address the tight labor markets of 2021 are almost the same as the ones we put forth two years ago, when no one knew what a coronavirus was. For employers, most of these are already being pursued, out of necessity. They include:

- Raising wages. In fact, this is already being done, but its impacts on growing the entire labor force have been limited.

- Searching more broadly for workers, relaxing requirements, looking at nontraditional workers. Looking outside local areas for a broader category of jobs.

- Investing more in training, hiring less qualified workers and training them up to acceptable skill levels. Clearly, this is a risk, but more Montana firms will have to take it.

- Reconfiguring job roles to find ways to make existing staff more productive, covering needed functions with the existing workforce.

- Recruiting future workers by connecting with middle- school-aged students to give them exposure to the nature of jobs they may otherwise know nothing about.

Other actions, such as automation and outsourcing of work, has been underway when feasible for decades, but recent shortages have pushed the envelope further. The lack of available workers, while not a pleasant challenge for employers, nonetheless may prod them to take steps to eliminate the “bad jobs” in their workplaces. These may be jobs with high physical burdens, long or inconvenient working hours and other aspects that make them less competitive in a seller’s market for labor services.

Action Steps for Policymakers

There is much that policymakers could do as well. Perhaps first on the list would be better management of the economy from the Federal Reserve and Congress. Current central bank policy has seemed to throw inflation concerns out the window and continues to push down very hard on its economic stimulus levers at a time when broad swaths of the economy are running at capacity. And new multitrillion-dollar spending plans in Congress won’t do anything to relieve pressure on labor markets either.

But there are steps that policymakers can make that will have a more lasting impact. The problem is that many items on this list are deeply unpopular, even if the logic of carrying them out is powerful. These steps include:

- Boosting the retirement age, which is effectively set by the age at which individuals become eligible for Social Security and Medicare. This needs to be done to make these programs more solvent anyway.

- Increasing female labor force participation. More flexibility and an order of magnitude increase in child care availability would help tap into an underutilized segment of the potential workforce.

- Fixing immigration policy. This traditional strength of the U.S. labor market has foundered on the rocks of political storms for almost a decade.

- Raising teenage labor force participation, currently at rates that are 20 percentage points lower than 40 years ago.

- Rethinking drug testing policies. Legalized cannabis is just one of many factors that are causing attitudes and policies to change.

- Reconsider occupational licensing requirements. These limit the ability of two-earner couples to relocate to states with more economic opportunities.

Few of these actions get much consideration, much less a majority of votes. Yet removing formidable obstacles to labor force growth, in light of demographic realities, will require some new thinking along these or similar lines.

Of course, what actually occurs to end labor force shortages may be something much more ordinary, yet much less desirable. That is a collapse in labor demand caused by an economic reversal. I think most of us would agree that the problem of too much demand is better than the problem of too little.