COVID-19’s icy grip left no corner of the state’s cities and regions untouched, yet it has unfolded in a way that bears little resemblance to previous economic downturns. A recession that has humbled once thought to be recession proof industries, like health care, while at the same time pumping up demand for housing and durable goods – which generally suffer when economic uncertainty spikes – throws a curve ball at historical patterns of economic vulnerability.

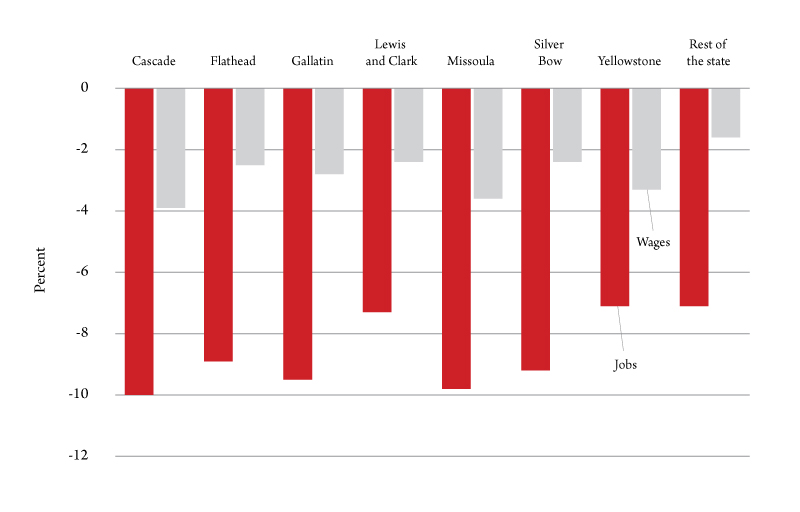

There have been two distinct phases of recent regional economic performance in Montana: pre- and post-COVID. The post-COVID regional pattern does not display the same degree of heterogeneity that was experienced in growth before the pandemic came on. The declines in payroll employment and in wages that occurred in the first two quarters of 2020 for the state’s largest urban areas, shown in Figure 1, display only slight differences between areas in what was a very painful contraction.

All of the 2020 declines shown in the figure were historically large. The small differences between cities largely stem from the relative size of the accommodations and food services in their local economies, which bore the brunt of COVID-related business declines. Public administration, which generally fared better, is another factor explaining regional differences, with Helena performing slight better in this regard.

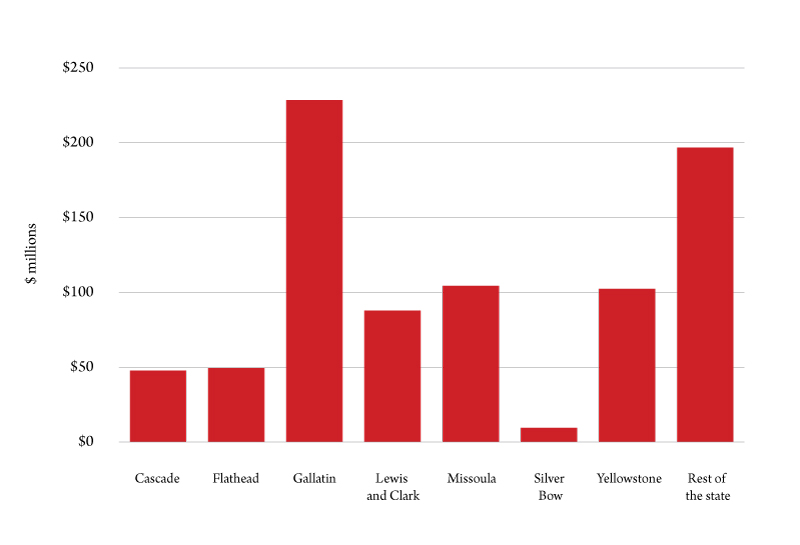

On the other hand, the pre-COVID patterns of growth between Montana’s larger counties continue to exhibit considerable variability. The growth in inflation-corrected (real) nonfarm earnings in 2019 across the state’s seven largest counties, shown in Figure 2, divides the urbanized counties into three groups.

The High-Flyer: Gallatin County

Gallatin County in southwestern Montana has been a high growth area for the better part of two decades, excepting the real estate collapse that toppled its growth during the Great Recession. Inflation-corrected nonfarm earnings, a good measure of local economic activity, has averaged annual growth of 6.3% since 2013. Only Madison County, immediately adjacent to Gallatin to the west, topped that growth mark over the same time period.

The Bozeman area’s strength in recent years has received a boost from high-tech, professional services and manufacturing growth. This adds to its base as a university town and as gateway to the Big Sky Ski Resort and Yellowstone National Park. Its airport, which is the state’s largest, has recovered 50% of the passenger volume lost when the pandemic first exploded, the strongest rebound in the state.

The Above Average: Flathead, Missoula, Yellowstone Counties

Three counties that differ considerably between each other have generally grown faster than the state average, although growth in Yellowstone County has tailed off of late. The factors driving their growth differ as well.

For years, Flathead County’s growth was mentioned in the same breath as Gallatin County, but its growth has fallen back in recent years. It shares Bozeman’s status as a gateway to a major national park (Glacier National Park lies just to the east) and is also home to a nationally recognized ski resort. After a big growth burst in health care in 2016 that was due in part to the expansion of Kalispell Regional Hospital, its health care sector has underperformed.

Overall growth in Flathead County has averaged 3.8% since 2013, second best of the state’s largest urban areas. Spending by nonresident visitors eclipsed wood products manufacturing in importance as an economic driver several years ago, although the latter’s presence remains significant, particularly in Columbia Falls. Flathead County also represents a key node in the state’s manufacturing landscape.

The pandemic-related closure of the Canadian border immediately to the north has been an extra challenge for the economy in 2020.

Missoula County’s recent growth history has moved in the other direction. Its economic performance, along with the performance of Ravalli County immediately to its south, suffered in the years immediately following the Great Recession, but both have improved considerably since. The second most populous county lost its claim as the second largest economy in the state to Bozeman, but that says more about the growth in the latter than weakness in Missoula.

While it has been hampered by the enrollment challenges at the University of Montana, growth in university research, and more significantly in its high-tech and professional services sector, has helped fuel recent growth. Its average growth of 3.6% since 2013 falls just short of Flathead County.

Yellowstone County, the state’s largest, has had growth challenges ever since the oil price collapse of 2014-15. Prior to that time, Billings enjoyed strong growth that reflected the economic conditions of the four-state region it serves as a commercial hub. Not just energy, but agriculture across the state enjoyed very good years in the aftermath of the Great Recession, with decidedly different circumstances in both sectors playing out today.

As a county with no oil reserves, Yellowstone’s connection to Bakken oil fields and other energy and mining activities is less apparent, but its numerous, high paying, mining, construction and other support services jobs have had a huge influence on the overall fortunes of the local economy. The Bakken’s thankfully brief, but severe, downturn in the months after the oil price turbulence of early 2020 creates more uncertainty for this part of the economy.

The strength of the goods side of the national economy in the midst of this downturn and the emphasis on supply and logistics plays to the strengths of the Billings economy. As pandemic disruptions ease, the region’s health care industry, by far the state’s largest, should get back on track as well.

The Rest: Cascade, Lewis and Clark, Silver Bow Counties

Three other urbanized counties in the state have had economic trajectories that more closely resemble the overall average. They differ in almost every other respect, however.

Cascade County is home to Great Falls, the urban hub and commercial capital of a large swath of north central Montana, including some of the most productive farmland in the state. It enjoys the stability of being host to a sizable military facility (Malmstrom Air Force Base), but has been challenged in recent decades in capturing its fair share of the economic migrants that have settled further south and west.

The education and information/media sectors of the economy have been more challenged by the pandemic than most, while the retail sector has held up a bit better. A better year for farm revenues, thanks in part to government support programs, is a plus for the local economy.

Lewis and Clark County’s economy, home to the state capital, has not been recession proof in this downturn, as has often been the case before. The shutdown in schools helped produced the opposite – a disproportionate contraction in government employment and wages that produced more pain than elsewhere. This was partially offset by strength in retail and stability in health care. But the largess of the CARES Act brought plenty of federal spending into Montana in general, which bodes well for Helena’s immediate future.

Silver Bow County, the smallest in terms of geography and population in the discussion thus far, has seen greater ups and downs in recent economic growth. Most promising in recent years has been its rising prominence as a visitor destination, which has been challenged by the pandemic. Its earnings overall have always been greatly influenced by the wages and bonuses paid by its remaining mining employers, and the recent strength in copper prices augers well for the immediate future for that sector.

The Rest of the State

It is, of course, impossible to paint a simple picture of the state’s 49 remaining counties in terms of their economic performance. Yet significant stories remain to be told. The oil patch counties on the state’s eastern border can expect to feel further fallout from the uneven performance of that commodity over the course of 2020, just as the coal producing areas bordering Wyoming have been challenged by the gloomier prospects for that economic driver.

Less noticeable perhaps is the profound influence of federal government spending and employment in many parts of the state, but especially along the northern border. Most of the growth in government jobs and wages that occurred in 2020 was outside the state’s urban areas. On the other hand, the out-migration of younger people toward cities and other opportunities from the state’s rural and frontier counties continues to present nonurban Montana with serious challenges in everything from housing to health care access.