2020 was poised to be a good year for tourism in Montana. The industry came off a banner year in 2019, which garnered $3.75 billion from 12.6 million visitors – 2.2% more visitors than 2018. As the year began, unemployment rates were at all-time lows; rates hovering around 3.5 percent, consumer sentiment was the highest it had been since 2005, and the economy was continuing its record months of expansion. In preparing for the summer peak travel season – about half of all visitors arrive between July and September – the biggest worry seemed to be the potential severity of the fire season. But 2020 has proved to be anything but a normal year.

The University of Montana’s Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research (ITRR) routinely monitors the tourism and recreation industries of Montana. They largely do this via on the ground surveyors stationed throughout the state. These efforts result in the ability to provide estimates of the number of visitors to the state, how much they spend, and how that spending impacts the state’s economy.

Recognizing a massive upheaval was on the horizon for tourism in Montana, and the impending inability to interact with visitors face-to-face, ITRR began a series of secondary information surveys. Its purpose was to gauge the potential impacts of the pandemic to Montana’s tourism industry, as felt by travelers and businesses. The series showed how concerns over health and the economy impacted the tourism industry, as the virus spread and governmental actions took hold.

The Traveler

March 11-15

The first round of surveys took place just as the first identified cases were being reported in the state. At the time, 59% of the 1,460 non-Montana resident respondents indicated they were at least somewhat concerned about their own health. Meanwhile, a larger portion (72%) indicated concerns for the health of their community. While these were moderately high levels of concern, they were small compared to the 88% who indicated concern over the economy. Forty percent indicated they were extremely concerned and 43% strongly agreed with the sentiment that the outbreak could increase the likelihood of a recession. However, likely attributable to the lack of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the state, Montanans were less likely to be concerned about their own health. Only 50% voiced concern about their own health and 66% for the health of their community.

Concerns about both one’s own health and the future health of the economy were likely to impact travel decisions, so respondents were asked to indicate changes to their upcoming travel plans. Prior to reports of the outbreak in the U.S., two-thirds of Montanans and non-Montana residents surveyed had already booked trips – including flights, hotels, or special events – more than 50 miles from home. At the time of the survey, 20% had canceled at least one of these booked trips due to the pandemic. In total, non-Montana respondents indicated they had canceled 10% of their booked trips and were still considering canceling an additional 17%. Booked trips to Montana fared better as only 3% had been canceled and another 8% were under consideration.

Montanans, who contribute substantially to the travel economy, appeared equally unlikely to cancel their trips, with almost half of their booked trips planned to take place within the state.

With the typical opening of Yellowstone National Park still a month out from this first survey and the opening of the Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier even further out, early indicators suggested if the pandemic remained at bay and actions to flatten the curve were taken quickly, Montana may pull through. However, while the cancellations to Montana remained in the single digits, the changing nature of the pandemic necessitated continued monitoring.

March 26-31

Two weeks later, the travel and economic environment both within Montana and across the country had noticeably changed. The 59% of non-Montana respondents and 50% of Montanans who had previously indicated concern for their own health were now at 84% and 76% respectively. Similarly, concerns for the health of their communities was also on the rise, with 93% of non-Montanans and 88% of Montanans now concerned. Nearly unanimous concern, in excess of 90%, across both groups was now being expressed for the state of the economy and the likelihood of a recession.

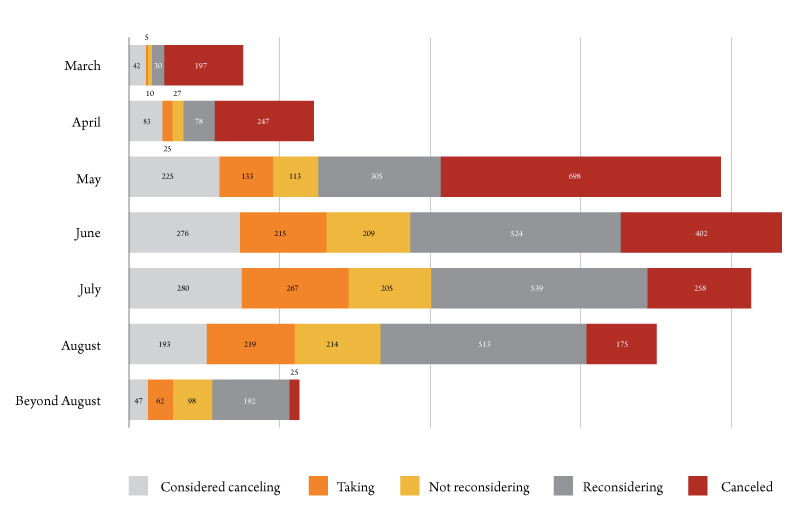

The combination of health and economic concerns, as well as the shutdown of major portions of the economy with stay-at-home orders, began to impact the upcoming travel season – kicking off following Memorial Day. At the end of March, the bulk of planned trips had been for May and June. While many respondents were canceling trips in March and April, they were holding off on fully canceling trips for later in the summer.

As of the end of March, it appeared the fate of the 2020 travel season in Montana was dependent upon how quickly the ability to travel could return to normal.

May 8-12

Just over a month passed between survey efforts and a lot unfolded during that period. Students at the University of Montana, Montana State University and other schools did not return to their respective campuses following spring break; younger students took up remote learning, residents began working from home or were laid off; a 14-day quarantine period was initiated in Montana for those arriving in the state; and the border between U.S. and Canada closed to nonessential travel.

While economic concerns remained high among the respondents, concerns over one’s own health and that of their communities eased somewhat, though still above 75%, even in the midst of all the disruption. This coincided with a phased reopening of Montana businesses and an end to the 14-day required quarantine. When asked about traveling to Montana following the lifting of the quarantine, over a third of nonresident respondents indicated they planned to make a trip to the state. Additionally, 81% of Montanans indicated they planned to travel around the state, more than 50 miles from home, at some point during the summer.

The eagerness to travel to and around Montana was evident, but not overwhelming. A second piece of data began to back up these responses. Visitation to Montana State Parks was up 25% over 2019 in June – this includes a 39% increase in May alone. However, this desire to visit and travel ran counter to the observations coming from larger destinations, and even from local businesses dependent upon these travelers.

The Tourism Dependent Businesses

Coinciding with the traveler surveys, ITRR reached out to tourism-dependent businesses to better understand the impacts the pandemic was having on their businesses. The late March survey found 63% of businesses reported zero bookings for April, 61% percent had zero for May, 49% for June, and 21% said they had zero bookings for July and beyond. The good news at that time was the numbers were declining as summer progressed.

However, it wasn’t just changes in actual bookings that were seeing a dive – 91% percent of the accommodation sector reported their inquiries were down, followed by 87% of outfitters and guides. As one survey respondent stated, basically by the middle of March, the phone just stopped ringing. Additional data showed that 66% of tourism-related businesses had to temporarily reduced their workforce, and 57% temporarily closed some or part of their business.

Respondents were asked if they would permanently close their business due to COVID-19: 79% percent disagreed with the statement, 18% neither agreed nor disagreed, and 3% reported that they would close. This included eight hotels, five outfitters/guides, eight tourism service businesses and two tourism support service businesses.

Businesses took the same wait-and-see attitude observed with visitors. However, due to high expenses and a reliance on contract-styled labor, this led to financial stress with uncertainties about the duration of the impact and the ability to receive continued assistance.

Looking Back on the Summer of 2020

With Labor Day now in the rear view and schools back in session, the data will soon be in on the toll the pandemic has taken on businesses and communities this summer. COVID-19 remains an ever-present part of daily lives, but the catastrophe that could have been the economic case for Montana may have been averted for some and at least reduced for others.

Montana may have been fortunate in its abundance of wide-open spaces as its major draw, and the willingness of visitors to see and experience it. In normal years, roughly 85% of visitors arrive in the state via car, truck or RV. So while the airline industry continued to struggle, many visitors found a way to get to Montana and escape their urban spaces.

The typical visitor to Montana was likely different this year, as travelers canceled their flights to large urban destinations and instead visited places like Yellowstone National Park. In fact, visitation to Yellowstone was up 2% in July and over 7% in August of 2020, compared to the same months last year. However, visitation to Glacier National Park was down more than a third in both months, as portions on the east side of the park remained closed. Undoubtedly, the spending profile of visitors this summer will have changed too, as visitors flocked to campgrounds rather than hotels and shopped for groceries versus dining in restaurants.

While the economic data is still coming in, health concerns remain rightfully high, even if tempered somewhat by time. A majority of residents typically understand and agree with the importance of tourism to the state’s economic well-being. Not since the aftermath of 9/11 has the average perception of the benefits of tourism compared to the costs been as low as it has this summer.

Prior to this summer, the average respondent disagreed that the state was becoming overcrowded because of more tourists. However, that has now changed to an agreement on average. Perhaps our sense of what is and is not a crowd has changed as social distancing has expanded our comfort bubbles. Whatever the reason, it demonstrates a potential fracture in need of rebuilding.

As Montana plans for a post COVID-19 economic recovery, bringing communities and residents together – those who are often the first line in welcoming visitors – will be vital if a robust tourism economy is to be reestablished and maintained.