Housing in general, and home ownership in particular, have always been visible, tangible evidence of economic success. Simply put, economic systems and economic leadership that cannot adequately house their populations are judged as failures.

Perhaps that is why the escalating cost of housing in recent years, both in absolute terms and relative to income, has inspired calls to action at the local, state and national level. Witness the efforts to reform Seattle’s homeowner dominated neighborhood councils, the recently failed measure in California to override local building restrictions along transit corridors and the bill sponsored by Sen. Elizabeth Warren to spend $50 billion annually to build affordable multifamily housing in urban areas.

There are plenty of policies in support of housing and home ownership in place already, and evidence of their effectiveness is unconvincing. Despite spending $120 billion per year on tax subsidies to subsidize home ownership through the mortgage-interest deduction and enormous interventions in mortgage markets, with government-supported enterprises like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, ownership rates in the United States are lower than many countries that do none of these things. When it comes to affordability, those policies arguably make the situation worse by super-fueling demand for larger and more expensive homes.

But those policies have been in place in one form or another since the 1930s. The acceleration in home prices that has led to housing cost issues today began in the 1990s and really kicked into gear during the first seven years of the previous decade, when home prices in Montana increased by 7.4 percent per year for eight consecutive years, mirroring the national trend (Figure 1). While often dismissed as a bubble – or an unsustainably high price driven by speculation and not the more fundamental forces of supply and demand – the sustained price growth that has resumed after the bust suggests otherwise.

The focus of research on housing price growth has been on policies at the local level. Housing regulations are easy to talk about, but harder to measure. The variants are endless, but commonly include (Gyourko and Malloy, 2014):

- Infrastructure requirements

- Height restrictions

- Caps on numbers of units

- Population growth limits

- Urban boundaries or green zones

- Restrictions on rezoning

- Super majority, voter or multiple jurisdictional approvals

- Minimum lot size requirements

- Delays in local government decision-making

To measure the extent of regulation in any local market, much less assessing whether or not regulation is becoming more or less prevalent, is a daunting task. Yet there exists ample evidence that local regulation has a significant impact on housing costs. This is clear from a comparison of housing prices (as shown in Figure 1) to published measures of construction costs by Glaeser and Gyourko (2002) and others. The fact that since the mid-1980s prices and costs have widely diverged, with prices rising to nearly double the costs supports the argument that regulatory restrictions have had important price impacts.

Why High Housing Prices Matter

Of course, even if housing markets were efficient and prices reflected costs, those prices might be more than some households can pay. This is particularly true in areas with high in-migration and high demand and in places with geographic obstacles like water or mountains – land prices would be reflected in housing costs. In such situations, one might expect that a more intense use of land through higher density development would mitigate such outcomes, but few Montana communities have embraced this approach.

Housing is an asset, and any force that pushes asset prices up or down necessarily has equal and offsetting impacts on buyers and sellers. But from a societal point of view, there are at least three different ways in which artificially high housing prices bring about outcomes that shrink the overall economic pie. At the local level, high housing costs affect labor supply to area employers, affecting the costs or even the viability of services – even schools – that form the fabric of urban life. High housing costs push lower-income families out to the fringe or even outside urban areas altogether, increasing commutes, transportation costs and environmental impacts.

High housing costs can also have consequences for overall economic growth. This is because areas of the country that have the fastest growth tend to have the lowest rates of new home construction and thus the fastest increases in housing costs. High housing costs effectively inhibit workforce mobility, which has played an important role historically in helping households cope with economic change. Lower mobility threatens to increase income inequality and lower overall wealth.

Housing Affordability in Montana

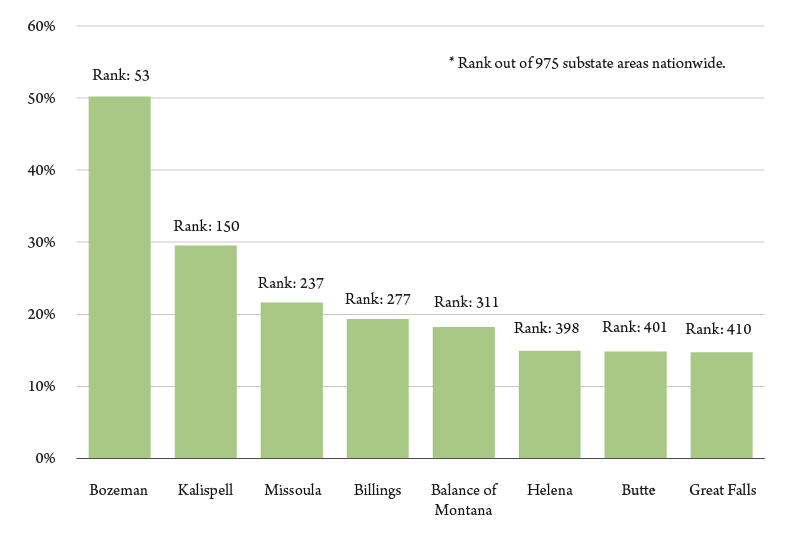

Is there a housing affordability crisis in Montana? Certainly there are parts of the state where prices have increased rapidly. Gallatin County has seen housing prices – as measured by the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s Housing Price Index – increase by 50 percent since 2012 (Figure 2). Yet the question of affordability needs to consider those prices in relation to incomes. Median household income in Gallatin County in 2016 was $60,439, the third highest in the state. The ratio of home prices to income, a simple measure of affordability, shows Gallatin County to be more affordable than most counties in northwest Montana, including Missoula.

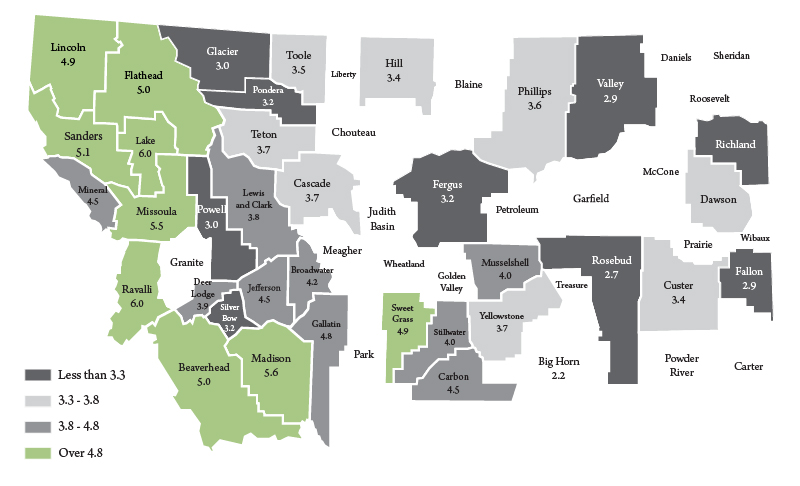

The price-to-income ratios for the 38 Montana counties for which adequate housing price data were available reveals that affordability generally worsens as one travels west (Figure 3). Median home sale prices in Ravalli and Lake counties, the least affordable in the state, were six times as high as median household incomes there. Higher incomes and more moderate prices produced lower ratios in counties like Yellowstone and the oil-producing counties of Richland and Fallon in the east.

Affordability has always been worse in the West – at least going back to the beginning of the past decade. But in the run up of prices before the Great Recession, affordability was significantly eroded. The resumption of stronger price growth since 2012 has again outpaced income growth, with affordability lower in most parts of the state today than five years ago. Despite this deterioration, prices relative to income are lower today than they were just before the housing bust 11 years ago.

The situation is a bit more restrained in rental markets. While rents have increased markedly since 2012, in 2017 the median renter household paid about 32 percent of their pretax income for gross rent in Missoula and about 31 percent in Gallatin counties. Both figures are reasonably close to the 30 percent threshold often used to define “housing stress” in household budgets.

Working Toward Solutions

The solution to housing affordability depends on one’s view of the problem.

To some people’s way of thinking, there may not be a problem with housing prices at all. Certainly in many Montana housing markets the level of prices relative to income falls short of what would be considered unaffordable. But even in the faster growing areas where prices are much higher, the regulations impacting new construction represent a sort of tax on development, which forces developers to pay the costs incurred for the congestion and inconvenience of construction and density.

The fact that tighter regulations so clearly serve the financial interests of existing homeowners by limiting the new supply that might compete with their homes in the marketplace, casts some suspicion on this argument. And it would be highly unlikely that the political process would produce just the right level of taxation of new development to produce an efficient outcome. But the thrust of this argument is that prices of housing are high because they should be high, and the solution to affordability is helping those without enough income to pay for it.

The argument that it is local housing regulation that is pushing prices up beyond costs has greater support in the data. The research we report in the accompanying article shows that a change in the housing market, occurring sometime in the late 1990s, significantly reduced the price response of housing supply, especially in western Montana. The slow supply response to historically high price growth, combined with high demand from strong economic growth, has pushed prices ever higher.

Tackling regulation is not easy, technically or politically. Rules governing housing development are overlapping – the elimination of a single rule by one jurisdiction may have little effect. And those rules exist because those with political power put them there. Solutions could come about through interventions of state government, which could override the political wishes of local communities in governing development. That seems a long way off in Montana, but such moves have gained traction elsewhere.

There are other facets to the problem to consider. Consulting firm McKinsey & Company estimates that productivity in the construction industry has stagnated since the mid-1990s, growing by just 1 percent per year compared to the 2.7 percent per year gains in the overall economy. Part of that malaise is probably due to regulation-imposed activities that add cost with little quality benefit. But the technology of construction, in particular stick-built homes produced on-site, has not taken advantage of the kinds of process innovations that have boosted manufacturing productivity by 3.6 percent per year since 1995.

High housing costs – defined as prices and rents that are higher due to artificially restricted supply – are emerging as a significant public policy issue. While the issue is not as acute in Montana, it has worsened in recent years. Crafting solutions that flow from an understanding of how high costs have come about is critical if we are to going to make things better.

References

Glaeser, Edward L. and Joseph Gyourko, “The Impact of Zoning on Housing Affordability,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 8835, March 2002.

Gyourko, Joseph and Raven Molloy, “Regulation and Housing Supply,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 20536, November 2014.

McKinsey Global Institute, “Reinventing Construction: A Route to Higher Productivity,” February 2017.