The unprecedented swift and severe declines in economic activity that have coincided with the outbreak of the global COVID-19 pandemic have not spared Montana. As recently as mid-February, when the Bureau of Business and Economic Research (BBER) was in the midst of its statewide economic outlook tour, Montana was at full employment and enjoying a third consecutive fiscal year of healthy state revenue growth. Declines since then have occurred too quickly to be adequately measured by the most comprehensive economic measures, but when those data become available they will depict a broad-based recession of greater magnitude than what was experienced in 2008-09.

BBER has conducted an analysis of this new economic trajectory to help achieve a better understanding of the economic challenges that governments, businesses and households will face in the coming months. The analysis must be considered preliminary because the fluidity and uncertainty of the evolving health and economic situation make it almost impossible to incorporate all of the relevant information.

The key driver for this analysis is the revision to the U.S. economic outlook between December 2019, when the virus was off the radar for most of us, to April 2020, when its effects have propagated to every continent on earth. The question posed by this analysis is: What does the revised level and composition of national economic activity mean for the Montana economy? Our principal findings are:

- In calendar year 2020, the Montana economy will suffer an average employment decline of more than 50,000 jobs (including payroll, proprietor and contract workers), which represents a decline of 7.3 percent. Job losses will exceed that average in the second quarter of the year, with some improvement expected in the final quarter.

- Personal income (not inflation-corrected) in 2020 will be $3.9 billion lower in Montana than was projected in December, a downward revision of 7.1 percent.

- Almost every major industry in Montana will have lower employment in 2020 due to the COVID-19 contraction, with job losses particularly severe for accommodations and food, retail, arts and entertainment, and personal services businesses. Job losses will be greatest in the northwest region of the state, but every region will experience a significant downturn.

- Stronger economic growth in 2021, and to a lesser extent, 2022 will mostly close the gap and bring economic activity back within range of the medium-term growth projection made before the crisis.

This final point is perhaps the most problematic. It is based on the expectation, described more fully in the next section, that the U.S. economic downturn will be pronounced, but also relatively short. The IHS Markit forecast on which this analysis is based foresees annualized growth kicking up strongly in the fourth quarter of 2020 to double-digit rates. Since an event like the current COVID-19 pandemic lies outside the ordinary experience of economic models, such projections must be treated with caution.

The April 2020 Projection for the U.S. Economy

Three basic questions are posed for forecasters concerning the impact of COVID-19 on the national economy: 1) How much will the economy contract, 2) How long will the contraction last, and 3) What will be the trajectory of the recovery? The last question pertains to the pace of growth coming out of the low point of the downturn – rapid, gradual or something in between.

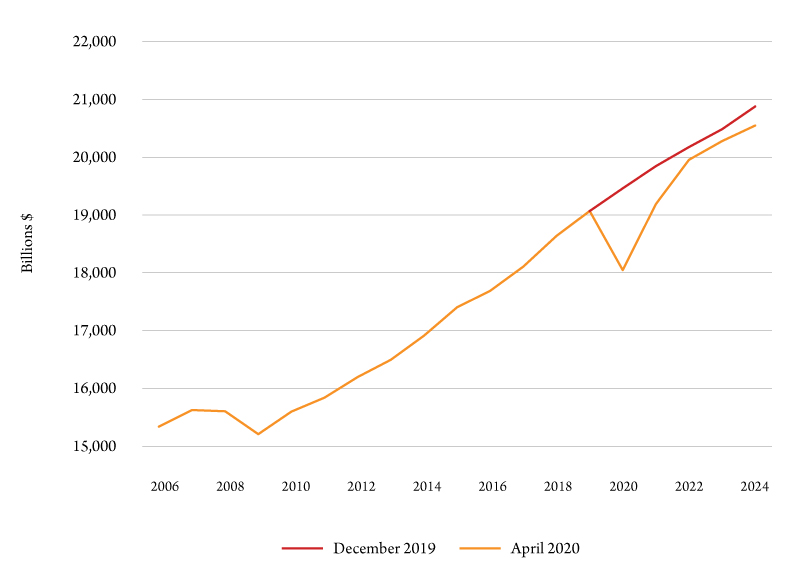

The answers to these questions for the IHS Markit forecast that the state of Montana subscribes to is apparent from the projection in Figure 1.

The economy is expected to experience a decline in inflation-corrected gross domestic product, the broadest measure of economic output, of 5.4 percent in calendar year 2020. As can be seen from the figure, this decline is much more rapid and much more pronounced than the contraction suffered in 2008-09. The decline is relegated to the year 2020 – the following year is expected to see a considerable amount of makeup growth. In the jargon of forecasting business cycles, the IHS Markit forecast calls for a “V” shaped recovery from the COVID-19 downturn, with economic activity approaching originally projected (December 2019) levels by the year 2022.

It is important to note that the estimate of a 5.4 percent decline in the U.S. economy in 2020 understates the impact of COVID-19 in at least two respects. First, it is an annual figure which averages severe declines in the spring with what are expected to be the beginnings of a robust recovery in the last three months of the year. The IHS Markit forecast of real GDP growth in the second quarter is negative 26.5 percent, at an annual rate.

Montana’s April 2020 Projection

BBER prepared two economic projections for the state of Montana using its policy analysis model based on the IHS Markit projections of the U.S. economy. The pre-COVID-19 projection was made based on the pre-COVID-19 U.S. forecast (December 2019). The impact of COVID-19 on the state is made by comparing this old forecast to a new forecast, based on the IHS Markit forecast released in early April. A comparison of these two Montana projections reveals sizable effects of COVID-19 in our state.

A few caveats before we present these comparisons. Since the BBER model is an annual model, we are not able to estimate impacts within each year. Annual estimates for the calendar years are available. Also, since the IHS Markit projection for the U.S. predates the most recent oil price volatility (resulting in WTI crude oil prices going negative), the full effect of chaos in those markets may be understated. Even though the full details of the CARES Act was not available for the preparation of the April U.S. forecast, the broad features of that legislation was anticipated and incorporated into these projections.

The steepness of the employment decline projected for 2020 for Montana (Figure 2) is striking, especially as it comes following nine years of steady growth. The gap between the two projections is more than 51,000 jobs, more than twice as large as the job decline between 2008 and 2010 that Montana experienced in the Great Recession.

The job total shown in Figure 2 differs from the payroll employment concept that is more commonly reported. We report jobs using the definition used by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, which includes payroll employment plus self-employed, proprietors and contract workers. Since some individuals hold multiple jobs, this estimated loss slightly overstates the number of people losing their source of earnings.

Our projection swings strongly upward beginning next year, with job gains in 2021 and 2022 taking the economy close to the level of employment that was projected at the end of last year. Even with this pace of recovery, the COVID-19 pandemic results in a three-year period with a smaller economy than was forecasted only four months ago.

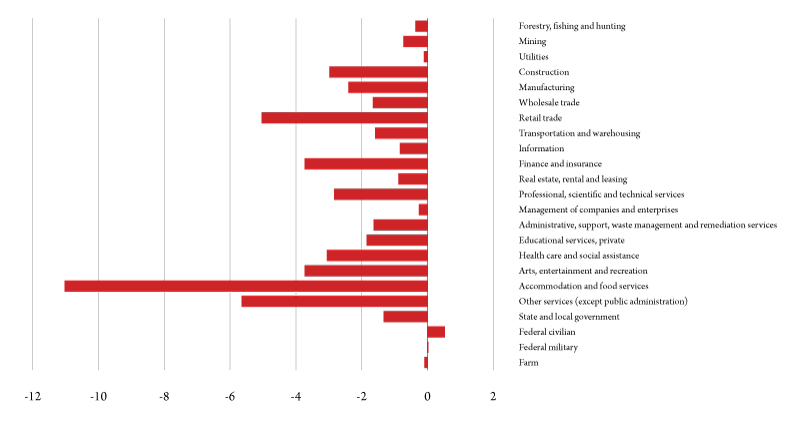

At the major industry level, the only sector that escapes job declines in Montana in 2020 is the federal government. Other industries that are less affected by the downturn include agriculture, mining and utilities. As shown in Figure 3, employment effects are particularly harsh for Montana employers in the accommodations and food, retail trade, and arts and entertainment industries.

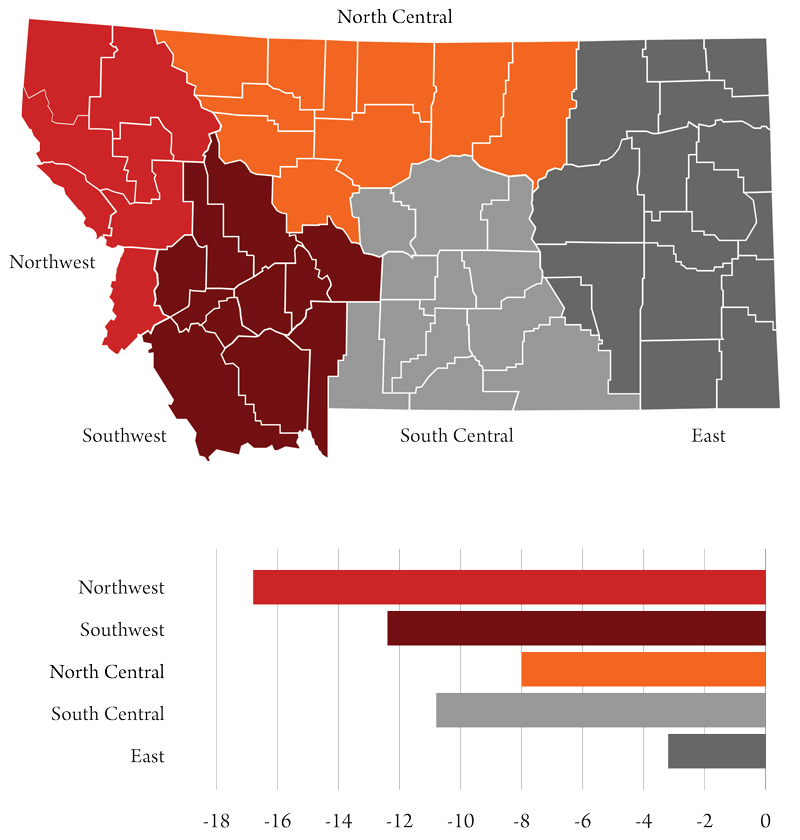

No region of the state escapes the effects of the COVID-19 economic downturn, as can be seen in Figure 4. While the job losses in 2020 are largest in the northwest region of the state, totaling over 16,000 jobs, population and employment in this region are highest overall as well. In percentage terms, 7.3 percent of jobs statewide are lost in the worst year (2020), with regional jobs losses ranging from 8.1 percent job declines in southwest Montana to 6 percent in the north central region.

Of immediate importance to businesses and governments in Montana is the effect of the COVID-19 downturn on income received by Montana households or personal income. While almost two-thirds of this income comes from earnings associated with employment, a sizable fraction comes from rent, dividends, royalties and rent. All of these sources have been profoundly disrupted by the economic upheaval associated with the pandemic.

The change in the trajectory of Montana personal income (billions of dollars, not inflation-corrected) due to the COVID-19 downturn is visibly larger than what occurred in the Great Recession. Compared to the projection made four months ago, personal income in Montana is projected to be $3.9 billion lower in 2020, a 7.1 percent decline. That represents a considerable decline in spending power for Montana households. It also is a significant erosion in the tax base for Montana, which relies more on the income tax for its general fund revenue than any other source.

Revisions to the Projections

Nothing that has occurred since we produced these preliminary projections for the Montana economy in April of this year has substantially altered the basic conclusions of our analysis. The COVID-19 recession is still expected to be much more severe than the Great Recession. It will not spare our state, and it will result in lower levels of employment for the next several years, compared to projections made at the end of last year.

But since the time our preliminary projections were made, new information has arrived that has yielded more insights which have changed some aspects of our projections. The dismal first quarter performance of health care was a surprise. So was the unexpected strength of employment in May. We now expect the downturn to cost the state about 70,000 jobs in the year 2020. And the speed of recovery is downgraded as well.

Conclusion

There is little doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic has produced a recession that is more severe than anything Montana has experienced in the postwar period. While events remain extraordinarily fluid and much uncertainty remains, even an optimistic forecast where growth resumes at the end of this year puts the state economy in a hole that takes years to refill. The risks to this forecast are biased, we feel, on the negative side of this projection, with still-to-be-learned aspects of this destructive virus challenging Montana’s economy in ways not yet anticipated.